Vincent Albarado aimed his cellphone camera as he stood between a Ferris wheel and a colorful carousel.

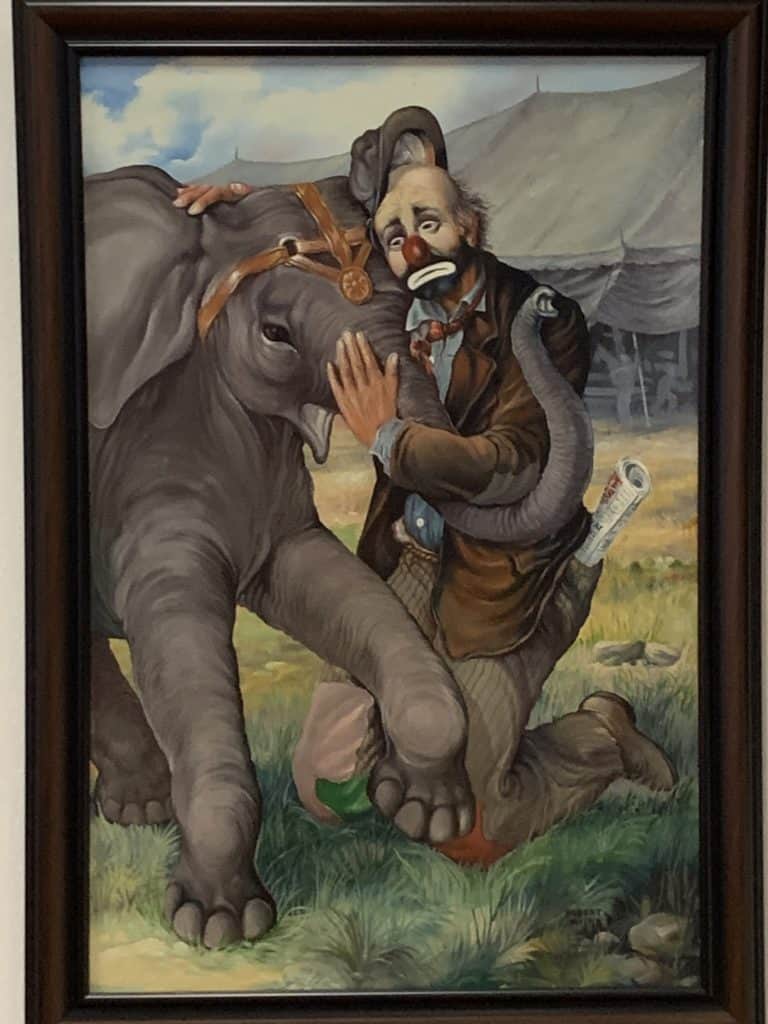

Snapping shot after shot, the Orlando resident marveled at the collection of old rides, photos and posters that fill the International Independent Showmen’s Museum, at 6938 Riverview Drive, just north of the Alafia River and Gibsonton, the longtime winter home of carnival and circus workers.

“I went on Groupon and saw this was one of the top 20 things to do in Tampa Bay,” Albarado said. “I never knew this existed, and I thought it would be interesting.

“I’m originally from Hawaii, and my family is coming to visit next year, so I’m definitely going to bring them here. It’s like an unusual gem with all this great American history. It’s amazing.”

The nearly 55,000-square-foot museum opened in 2013.

Doc Rivera, a former carnival and circus worker who has also owned a traveling show and food trucks, has meticulously assembled each exhibit – from the 1958 tugboat ride to the 1950 American Beauty Carousel – and runs the operation.

Every artifact in the museum was donated from former show owners and workers from across the U.S. and around the world, and benefactor Jim Frederickson donated $1 million to open the showcase dedicated to traveling show folks.

“At first, there was just a big pile of stuff on the floor,” Rivera said. “There were no exhibits built. I put it all in a systematic order the general public could relate to and added some videos. I got involved, because I’m a member with the International Independent Showmen’s Association – which oversees the museum – and they needed somebody to take over, someone who had previous carnival experience.

“I was in the business for 50 years, and I’m a historian, so it was a good fit.”

Read: Exploring Florida’s Hidden Natural Gems: A Unique Adventure

Rivera’s half-century of experience began in his native Indiana, when he was 14. He started with Drago Amusements in Kokomo. He was too young to operate the rides, but old enough, he said, “to tear ’em down and set ’em up.”

“For a while, I was a ‘ball boy’ – the person who sets the milk bottles up so they could knock ’em down” with a pitched ball, Rivera said. “I’d go home with bruises all over, because the balls would ricochet. Sometimes, the drunks would hit you on purpose.”

By his late 20s, Rivera had enough experience and capital to establish his own traveling show in Charlotte, North Carolina. The show was called Metrolina, after a nickname for the Charlotte region.

Metrolina was in operation from the early 1960s to mid-1970s. After selling the business, Rivera switched to operating individual rides and food trailers.

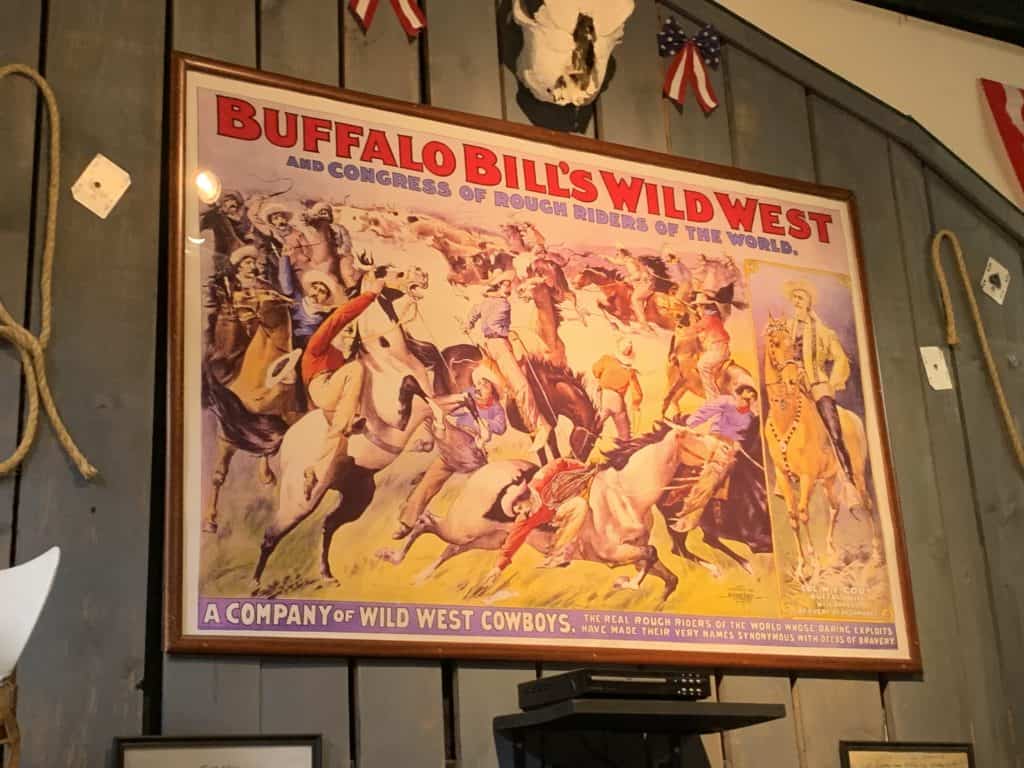

Rivera traced the popularity of carnivals and circuses to the 1920s when Eddie and Grace LeMay were traveling from the Midwest to Miami.

“They did portable restaurants,” Rivera said. “They were coming down U.S. 41, which was just a two-lane road then, with no roadside services available. They stopped along the banks of the Alafia River and, legend has it, that Eddie cast his line in, caught their dinner in 15 minutes, and they fell in love with the place.”

“They told everyone up north about Gibsonton.”

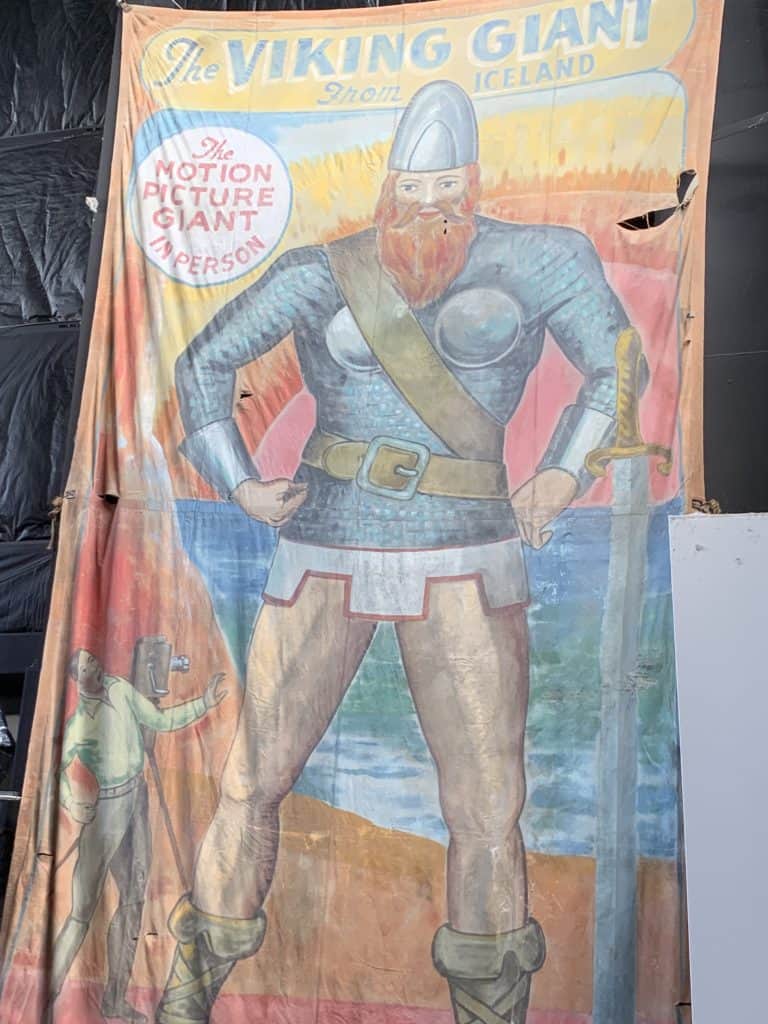

Soon, Al and Jeanie Tomaini came south and built boat houses, a bait shop, tourist cabins, and restaurants, Rivera said. On the traveling show circuit, the Tomainis were known as “The World’s Strangest Couple,” as Al claimed a height of 8 feet 4 inches while Jeanie was 2 feet 6 inches.

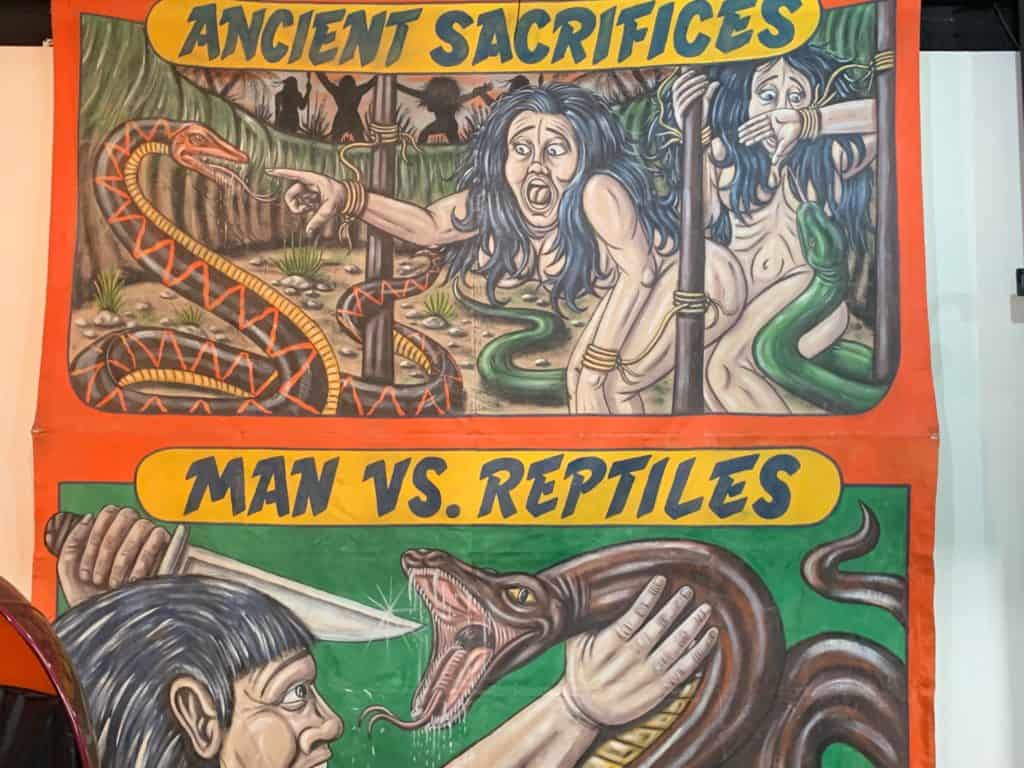

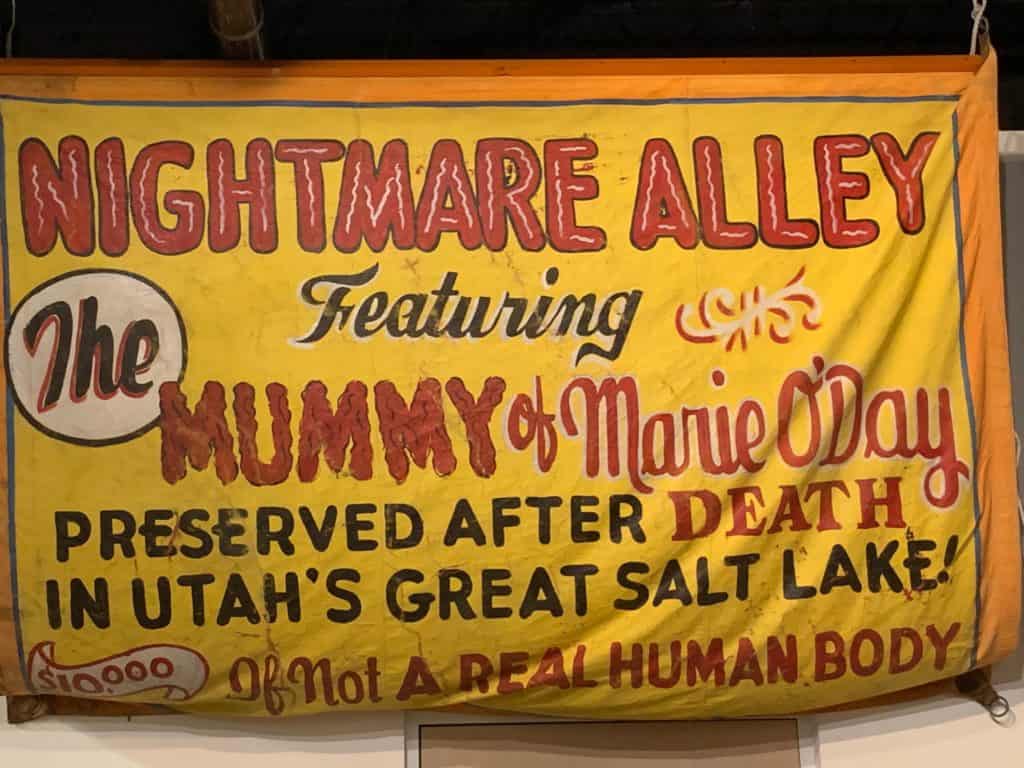

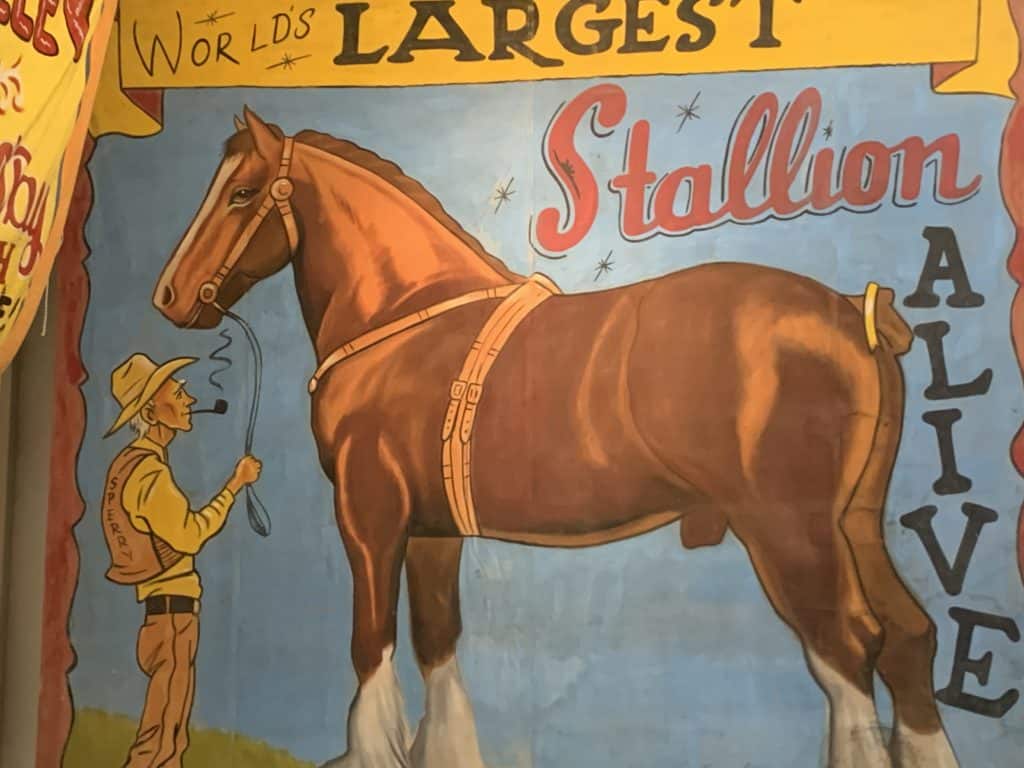

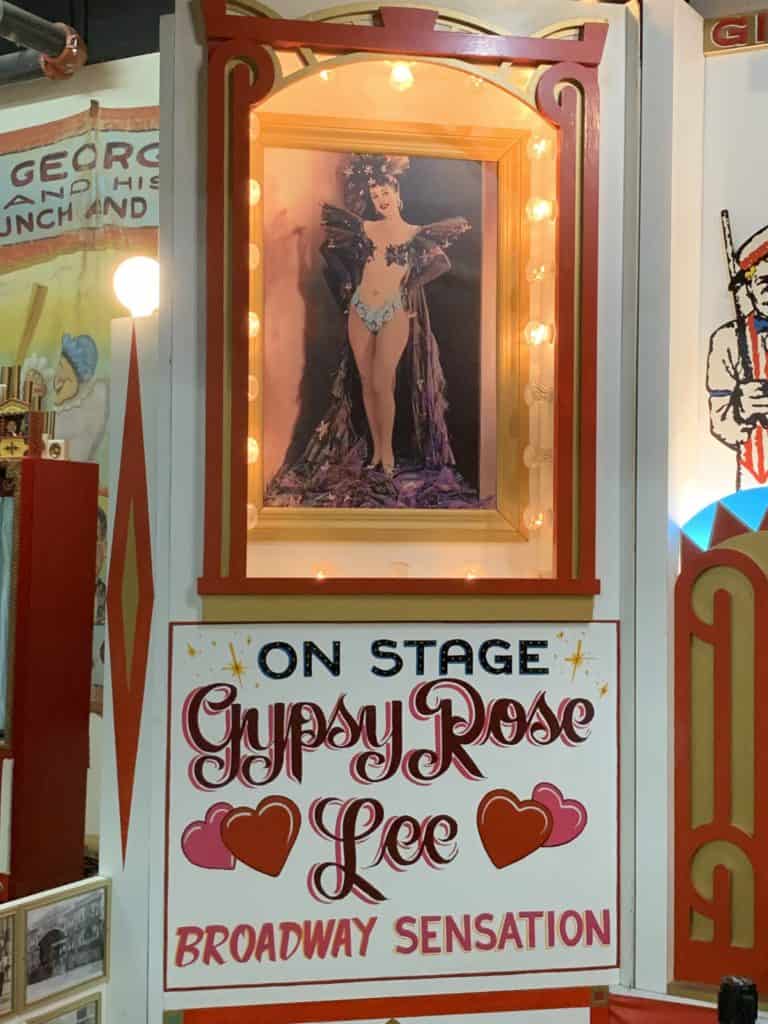

Word spread among the traveling show community about a place where winter was practically nonexistent and the human oddities that helped make carnivals famous – performers billed as The Bearded Lady, The Monkey Girl and the infamous Lobster Boy – could go about their lives without people staring.

The area’s Residential Show Business zoning laws allowed traveling show workers to let elephants roam freely in their front yards, practice trapeze techniques and store carnival rides and other accessories on their properties. For decades, Gibsonton was known as the unofficial sideshow capital of the world.

“It’s impossible to equate the history of America without considering the history of traveling shows,” Rivera said. “The Ken Burns documentary (“The Circus”) told the story of big railroad circuses that employed up to 1,200 people. They generated so much income, they were on par with the steel companies and railroads.

“At one time, there were about 200 railroad carnivals and circuses. Today, there is one.”

The decline of traveling shows can be traced to a drastic reduction in railroad lines, as well as the advent of television, Rivera said.

The story continues after the image galley. Please click each image to see a larger version.

“The 1950s signaled the decline of our way of life,” he said. “TV was the main thing, really.” People didn’t have to get off their rear to be entertained anymore. “Nowadays, you can play on your iPhone.”

Rivera takes seriously the responsibility of preserving the rich history of traveling shows. Besides being the museum’s curator, he offers tours, while keeping the exhibits running and the bathrooms clean.

David Holzapfel, 55, a friend of Albarado’s, was appreciative of Rivera’s efforts and beamed as he strolled through the museum.

“I never knew this existed,” he said. “It’s really an amazing experience. People my age remember what it was like to go to the circus. It’s fun to reflect back. Honestly, you’ve heard about The Bearded Lady, but you don’t know the history behind it. That’s what’s really cool.

“I hope this place stays here forever and ever.”

For information about the museum, visit www.showmensmuseum.org or call (813) 671-3503.

Android Users, Click To Download The Tampa Free Press App And Never Miss A Story. Follow Us On Facebook and Twitter. Sign up for our free newsletter.