Lars Schönander

With the Federal Reserve’s first meeting of 2022 set for Wednesday, talk of surging inflation and how to deal with it is back in headlines. When the government tried to control inflation in the 1970s, it caused an unemployment crisis that lingers in the American imagination as one of the worst economic periods.

The all items index increased by 7.0% over the past 12 months, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The index, for context, is the highest level view of inflation across all the various categories BLS tracks for price changes.

For example, BLS has an index for change in only food prices and an even more specific index for the price of dairy products as an example of a sub index. The “12-month percent change” for the all-item index is typically referenced when a single number is listed for inflation as it’s the broadest view of inflation. This one number, however, does not tell the whole story of how inflation affects workers.

As usual, concerns about inflation are leading to signals from the Fed about rate hikes. The last time major rate hikes were used to quell inflation was from 1979 and 1982 during the end of the Carter administration. The hikes were known as the Volker Shock, as Paul Volker was the head of the Federal Reserve at that period and specifically enacted these policies to quell rampant inflation.

Unfortunately, the rate hike also caused recessions due to a decrease in the money supply, and the result was unemployment. At the peak of Volker’s tightening policies, the federal funds rate was nearly 20%. For context, today’s federal funds rate is 0.25%. As for unemployment rates, in October 1979, unemployment was 6.0%, in November 1982 it was 10.8%. It was only after October 1987 when it fell below 6.0%.

We are in a similar situation with fears of inflation. But unlike then, we can learn from the past and enact policies that can fight inflation while not harming workers compared to brute-force rate hikes by first understanding today’s inflation situation, and then various solutions other than rate increases.

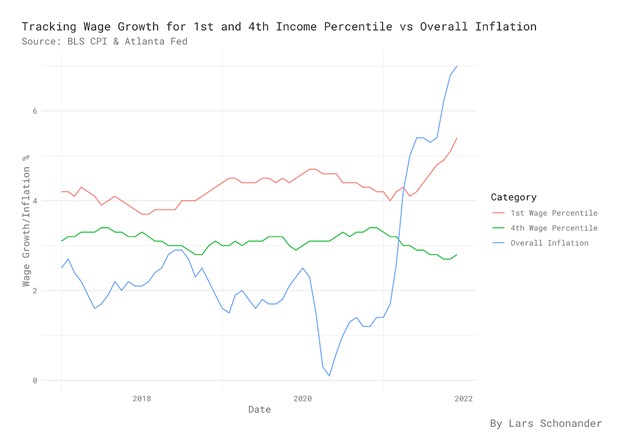

To understand the actual impact inflation has on a given worker, one needs to cross-reference wage growth data as well, to see how much inflation is actually eating up gains. Despite the usual rhetoric that “inflation actually hits the poor the worst,” when inflation data is referenced with wage data from the Atlanta Fed, the result tells a slightly different story.

Wages grew by 5.4% for the first (the lowest) percentile of income, while for the 4th quartile (the highest), wage growth was only 2.8%, according to December 2021 wage growth data from the Atlanta Fed. The quartiles are based off the Current Population Survey, which is a component of the U.S. Census. One of the items CPS collects is the earnings of households. The quartiles then are constructed from the wages collected, with the lowest 25% being the 1st quartile, and likewise the highest 25% being the 4th quartile.

By joining the wage data from the Atlanta Fed with the 12-month percentage change, Consumer Price Index and selected categories from BLS, a more accurate picture can be painted of who inflation actually hurts by tracking increases in wages versus inflation for the lowest and highest quartiles of income. To see in recent years how this played out, below is a chart of all item inflation versus wage growth with the first and fourth percentile of income from 2016 to the end of 2021.

Despite the increase in inflation over the past few months, the first income percentile in wage growth has done reasonably well. Wage growth in 2020 for the lowest percentile stayed consistently above 4% since July 2018, and from May of 2021 to December 2021 climbed to 5.4%. In contrast, wage growth for those highest in income in the same period fell. At the end of November, wage growth for those in that percentile was 2.8%, which represents a tiny shift back upwards in growth for wages in the highest percentile.

The increase in wage growth for lower-wage workers reflects various economic facts on the ground. Part of the “Great Resignation” is that lower-income workers simply have more options around due to surges in hiring for certain roles. Why go work for a store with a federal wage of $7.25, when you can work for Walmart for a wage of likely $16 on average, or for Amazon for a wage of $18 an hour?

This finding can also be found broadly for those without college degrees with the SCE Labor Market Survey from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. By specifically looking at reservation wages (the minimum wage a worker desires to participate in the labor market), for those without a college degree, it has gone from $48,778 in March 2020 to $60,117 in November 2021, an increase of 23%.

Unfortunately, the voice of actual workers is typically ignored in these debates. Instead, mainstream economic commentators are worried about strong wage growth and the millions of workers quitting their jobs. Complaints about wage growth are unfortunately over-represented compared to the economic facts regarding the increasing wages of lower income workers. Hence the focus on rate hikes as a tool for stopping inflation, versus alternative ideas.

To go back to the past, in World War II, the U.K. suffered from a similar problem where inflation was growing but eliminating it would cause more problems than solve them. In John Maynard Keynes’ work, “How to Pay for the War,” he thinks through the problem of how to fight inflation and control consumption while minimizing harm to the working class. Some of these solutions with modification can be done today.

As increases in spending tend to drive inflation, one method of minimizing spending is providing more options of deferred saving, or if needed for higher levels of income, mandatory saving. For example, limits on 401k savings could be raised to defer income from now into the future. For slightly more exotic methods, an expansion of TreasuryDirect, a platform by the Treasury that allows individual consumers to buy various bonds directly from it, could work.

One can imagine, for example, a temporary option to convert a percentage of one’s income into Series I Savings Bonds, which are guaranteed to be protected from inflation and return right now at 7.12%, or into a Series EE Savings Bonds like product, which have a lower interest rate, but guarantee a double return if one sells after a defined period of time. There are even more exotic rollovers one might do after the threat of inflation is minimized, you could let them keep in their treasury account as the given bond category, convert the saving over into a 401K for retirement with the saved money not being taxed.

On the side of taxation, one can design consumption taxes to deflate certain markets without targeting the working class. Luxury taxes on certain goods, like second homes or first homes above a certain price. New York City has a mansion tax as an example. These taxes could be designed like the George H. W. Bush-era luxury taxes, albeit without the loopholes.

For a more targeted approach, something we can hone in on is the price of food. Inflation for food went up by 6.1% in November 2021, but there is a way to alleviate this. The U.S. maintains various price support programs to hold up the price of certain goods.

Temporarily modifying the reference price for the various commodities covered under these programs could be a targeted way to deal with inflation with food. Considering that all inflation sans food and energy is 4.9% in November 2021, a more targeted approach may be warranted.

Policymakers can design methods for fighting inflation without harming the gains of the working class. It is important to take inflation seriously, but serious enough to realize that brute force solutions are not fit to solve the problem.

Visit Tampafp.com for Politics, Tampa Area Local News, Sports, and National Headlines. Support journalism by clicking here to our GoFundMe or sign up for our free newsletter by clicking here.

Android Users, Click Here To Download The Free Press App And Never Miss A Story. It’s Free And Coming To Apple Users Soon