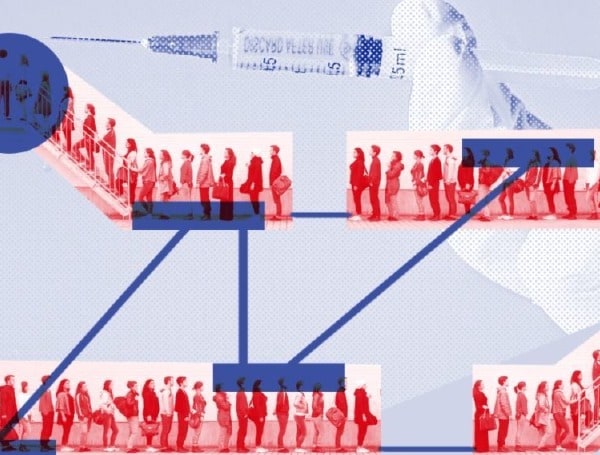

With front-line health workers and nursing home residents and staff expected to get the initial doses of COVID vaccines, the thornier question is figuring out who goes next.

The answer will likely depend on where you live.

While an influential federal advisory board is expected to make its recommendations later this month, state health departments and governors will make the call on who gets access to a limited number of vaccines this winter.

As a result, it’s been a free-for-all in recent weeks as manufacturers, grocers, bank tellers, dentists and drive-share companies all jostle to get a spot near the front of the line.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted 13 to 1 this month to give first vaccination priority to health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities once the Food and Drug Administration approves one or more COVID-19 vaccines for emergency use. The advisory committee is expected to provide further details of its list of prioritized recipients before year’s end.

Its next recommendations are likely to focus on prioritizing people who keep society functioning, like workers in food and agriculture, public safety and education. Older people and those with chronic diseases are also considered high on the list.

But because early supplies of vaccine are limited, tough choices lie ahead, such as: Is it more important to prioritize teachers who come into contact with many people each day, or farmworkers, who can’t work remotely and provide the country’s food?

“We have to be mindful of equity issues, comorbidities and the likelihood of death versus survival, even within these essential workers,” said Mitch Steiger, a legislative advocate for the California Labor Federation. There will be “a lot of really tough conversations and a lot of different competing principles.”

Initially, states won’t get enough vaccine doses to cover even their top-ranked groups.

In California, a state of 40 million residents, the initial shipments of around 1 million doses won’t come close to covering everyone at the front of the line. More than 2 million people fall into the Phase 1a category of vaccine distribution, which covers only those at risk of getting sick at a health care or long-term care setting.

Even within that health worker category, there’s jockeying to get to the front of the line, with pharmacists and dentists arguing for priority.

Dr. Laurie Forlano, deputy commissioner for population health at the Virginia Department of Health, said the state has been hearing from numerous parties via letters, phone calls and virtual meetings as it decides which “critical workers” will follow the initial bunch in getting vaccinated. “It is complex,” she said of the undertaking. “But it is not new for public health to make these decisions.”

States have already signaled different priorities.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said that after nursing home residents and front line health workers are inoculated, the state will try to vaccinate people 65 and over and residents with significant illnesses.

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear said grade school teachers should be next in line after health care workers and nursing home residents, along with first responders and adults with significant illnesses.

Pennsylvania will include “critical workers” and people with high-risk conditions at the top of its priority list, along with health workers, nursing home residents and staff and first responders, according to state health department spokesperson Rachel Kostelac.

Nationally, disease advocacy groups point out that people with some preexisting conditions are at a greater risk of death if they become infected with the coronavirus. The American Diabetes Association published an opinion piece advocating for its patients; the National Renal Administrators Association wrote to federal regulators saying kidney patients should be prioritized.

Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said he expects states to largely follow the committee’s priority list. But it’s unclear how much detail the CDC committee will provide in its next round of recommendations — such as which “high-risk individuals” and critical workers to include.

Leaving some flexibility for states is good, Plescia said, because they may differ on ways to vaccinate people efficiently. For example, some states may be home to large factories where people are at higher risk and could get vaccinated on-site.

That’s also where lobbying comes into play.

“Priority 1a for us is getting our employees into that ‘priority 1b’ priority group,” said Bryan Zumwalt, executive vice president of public affairs for the Consumer Brands Association, which represents companies that make thousands of household products, from toilet paper to soda. Of the membership’s 2.3 million employees, 1.7 million are considered essential, he said.

“Workers at our companies are making life-sustaining products,” Zumwalt said. The association is reaching out with letters to state health departments, but Zumwalt said the process would be easier if there were a uniform national priority order for the vaccine, instead of letting states have final say.

These companies are dealing with absenteeism rates averaging 10%, he said, which could cause delays in producing food and other key products.

“When one worker tests positive, an additional five to 10 workers have to be taken off the production lines,” he said.

In Idaho, a COVID-19 advisory board decided this month that after health workers and nursing home residents and staff, first responders such as police and firefighters, and grade school teachers and staff should get the shots, followed by correctional facility staff, then food-processing workers, grocery workers and the Idaho National Guard.

Dr. Elizabeth Wakeman, an associate professor of philosophy at the College of Idaho, and a member of the board, had told her colleagues that it made more sense to vaccinate with the aim of slowing virus transmission rather than ranking groups on their value to society.

That would put food-processing workers ahead of grocery clerks, because there’s more room to maintain distance and better ventilation in a grocery store, Wakeman said.

There’s also pressure to quickly protect food service and farmworkers. Diana Tellefson Torres, executive director of the United Farm Workers Foundation, said farmworkers are both essential and deeply at risk. They may work outdoors where transmission risk is lower, but they often live and ride to work with many people outside their immediate families, she said.

Most farmworkers are undocumented immigrants who lack health insurance and “might not even know they have underlying health conditions,” said Tellefson Torres, who sits on California’s Community Vaccine Advisory Committee. “There’s a lot of vulnerability.”

It’s almost time for the winter citrus crops to be harvested in California, and the lettuce needs to be picked in Arizona.

“It’s important to ensure that the community of individuals who provide food for this country, the food at each one of our tables, is also taken into consideration as a top priority,” said Tellefson Torres.

In the opening week of California’s legislative session, one of the first pieces of legislation to be introduced argued that the food-supply workforce should be first in line for vaccines and rapid tests.

The International Association of Fire Fighters, a union representing 322,000 firefighters and emergency medical personnel, is pushing to include its members as among the first to get access to the vaccine, arguing that firefighters provide emergency medical services that bring them into people’s homes and other closed spaces.

Airline employees also want to be quickly vaccinated.

Pharmacists, too, have also been making their case. While the ACIP included pharmacists in its Phase 1a health worker category, each state interprets the recommendations differently based on its vaccine supply, noted Mitchel Rothholz, chief of governance and state affiliates for the American Pharmacists Association, which is urging states to keep its members atop the list. “It’s a race for who gets the vaccine first,” he said. “Everybody wishes there was enough supply for everyone right out of the gate, but that’s not the situation.”

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Kaiser Health News (KHN) is a national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.